Food & Climate

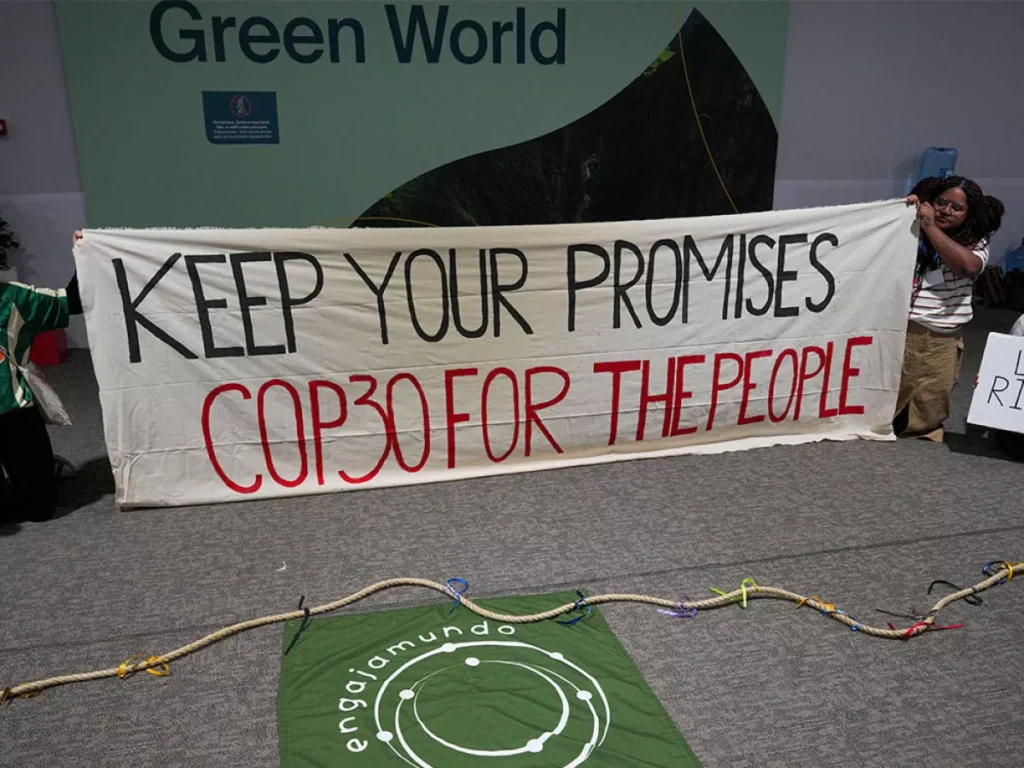

After two weeks of negotiations in Belém, Brazil, the COP30 U.N. climate summit delivered mixed outcomes, Indigenous delegates say. The event saw the largest Indigenous participation in COP history and landmark pledges made, but also heated protests and last-minute disappointments.

“The summit was historic for Indigenous peoples, and this is the result of the Indigenous struggle working to be at this COP not only in numbers but also in quality of participation,” said Kleber Karipuna, executive coordinator of the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB), one of the main Indigenous organizations in Brazil.

“Not everything has been won as we expected — much more Indigenous lands [still need] to be demarcated”, according to a report seen by Food & Climate.

A major outcome of the summit was the Intergovernmental Land Tenure Commitment (ILTC), a historic pledge to recognize Indigenous land tenure rights over 160 million hectares (395 million acres) — an area the size of Iran — across tropical forest countries, including Brazil, Colombia and the Democratic Republic of Congo, by 2030.

“It is one of the most positive outcomes we hoped to achieve at COP30,” Kleber said. “In Brazil alone, 63 million hectares [156 million acres] of Indigenous lands are pledged for protection, management, and land ownership.”

Forest tenure funders pledged at COP30

The Forest Tenure Funders Group (FTFG) announced a renewed pledge, totaling $1.8 billion, to support Indigenous peoples, local and Afro-descendant communities in securing land rights over the next five years.

Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva also signed decrees for 28 quilombos — rural Afro-Brazilian communities — across 14 states in Brazil, recognizing these areas as being of social interest and completing a step toward titling the territories.

The COP30 host also announced the demarcation of 10 Indigenous territories, encompassing diverse peoples, biomes and regions.

The decision follows a recent analysis that showed designating public forests as conservation units or Indigenous lands could prevent up to 20% of additional deforestation and reduce carbon emissions by 26% by 2030.

The renewed $1.8 billion FTFG pledge, which aims to strengthen stewardship of terrestrial ecosystems, including forests, explicitly emphasizes Afro-descendant peoples, women and youth. Their roles and participation were recognized for the first time in four draft texts related to the deal to collectively mobilize against climate change (the Mutirão Decision), climate adaptation, the just energy transition, and a plan of action on gender.

Victims of forest protection

Delegates like Ana Lucía Ixchíu Hernández, a Maya K’iche’ leader from Guatemala, called for governments to address impunity against the killings of land defenders who protect the forests that are critical to mitigating climate change impacts.

During the last week of COP30, an Indigenous Guarani leader in Brazil was killed, reportedly by armed individuals linked to private security forces employed by local landowners. A recent report shows that Colombia recorded the highest number of documented killings of environmental defenders last year, with 48 deaths, while Guatemala saw an increase from four in 2023 to 20 in 2024.

Hernández — who recently participated in the Yakumama Flotilla, a 3,000-kilometer (1,860-mile) journey down the Amazon from the Andes to COP30 to demand better participation of Indigenous peoples be in climate negotiations, and who has lived in exile since 2021 for her advocacy — said COP summits do very little to actively ensure protection of Indigenous land defenders.

“We are not criminals, we are not terrorists, we demand to be alive to continue doing our work for life and biodiversity,” she said.