Food & Climate

A new study published in Nature Climate Change reveals how plant genebanks, home to millions of genetically diverse plants around the world, can help speed up the process of breeding crops better suited for climate change, like draught.

The researchers used sorghum, a grain grown for food, fuel, and livestock feed, to test a new method called environmental genomic selection.

“Climate driven pressures on food crops touch every country on our planet and this technique holds promise for making more use of our global genebanks,” said co-author Michael Kantar of the UH Mānoa College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resilience (CTAHR), according to a report seen by “Food & Climate” platform.

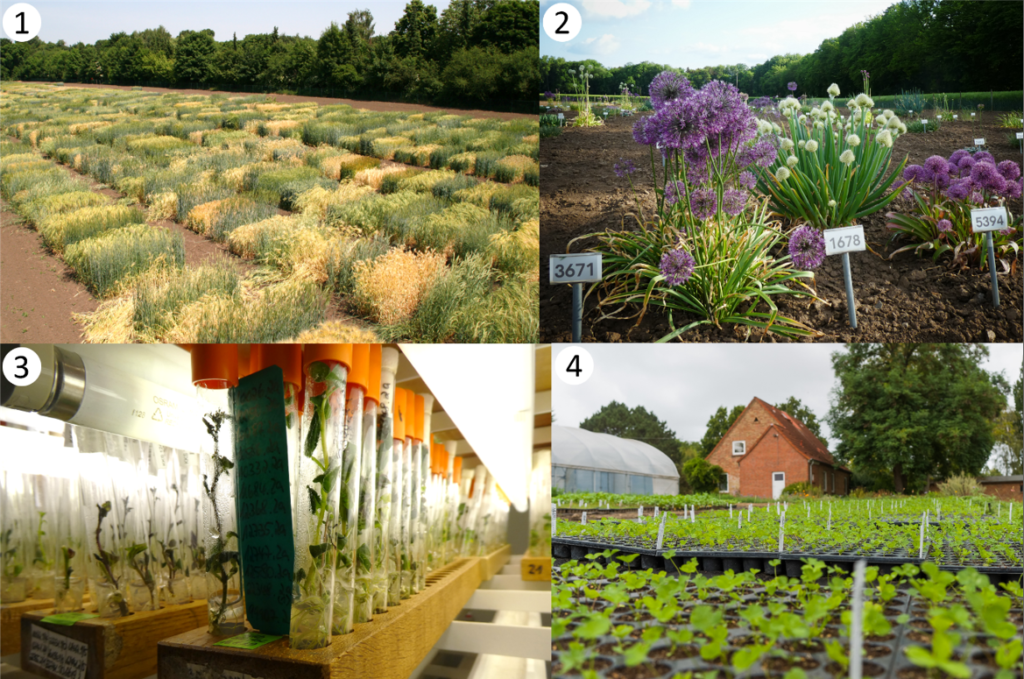

Plant genebanks were created by started by the mid-twentieth century as a reaction to the rapid loss of agricultural biodiversity, mainly due to the replacement of landraces by improved varieties.

This replacement was made possible by enormous energy inputs into agrarian systems in the form of machinery, fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, irrigation, protected cultivation, etc., which make environmental conditions more uniform, thereby allowing a limited number of improved varieties to be grown everywhere, replacing landraces adapted to microenvironments, local cultivation methods, and cultural elements of use.

It has been estimated that 70% of currently cultivated crops are of foreign origin, while the traditional crops indigenous to each area are disappearing.

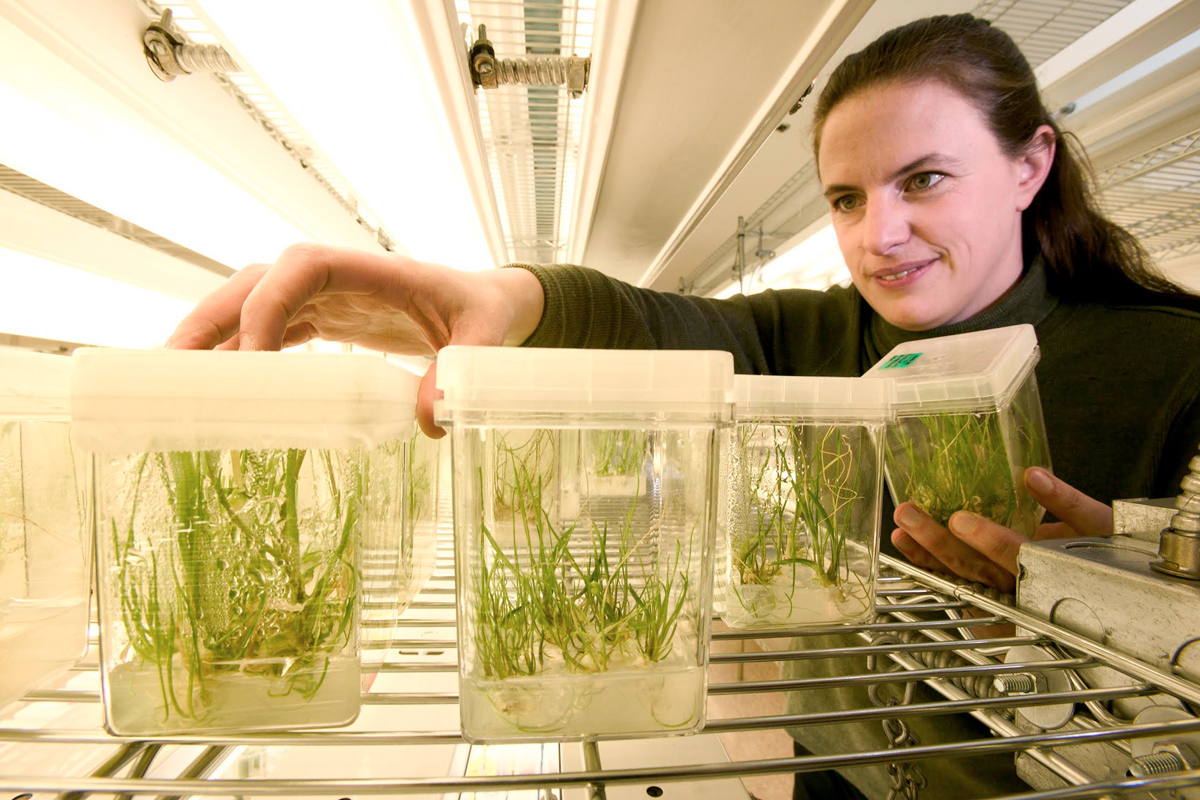

Plant genebanks are living libraries

According to the new study co-author Michael Kantar of the UH Mānoa College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resilience (CTAHR), plant genebanks are essential for protecting the genetic diversity of food crops.

These “living libraries” store seeds and other genetic material, providing a vital resource for plant breeders working to develop new crop varieties that have a range of traits from drought resistance to disease tolerance.

The researchers used sorghum, a grain grown for food, fuel, and livestock feed, to test a new method called environmental genomic selection. It combines DNA data with climate information to predict which plants are best suited for future conditions.

“It can be applied to any crop that has the right data, these include sorghum, barley, cannabis, pepper and dozens of other crops,” said Kantar.

The approach also saves time. Instead of testing thousands of plants in the field, scientists use a smaller, diverse “mini-core” group to forecast how crops will perform in different environments. This helps breeders quickly select the best parents for new, climate-resilient varieties.

“This method will help us keep pace with the hotter temperatures and increased risk of flooding from Earth’s changing climate and help develop new varieties to ensure food security,” Kantar said.

Researchers discovered that nations with high sorghum use may need genetic resources from other countries to effectively adapt to climate change, stressing the value of global teamwork in securing the world’s food supply, according to “PHYS. org.

75%of crop genetic diversity has been lost

According to the FAO, 75% of crop genetic diversity has been lost since the 1900s, and just around nine crops account for 70% of global food production. Restoring and safeguarding agrobiodiversity is not just about conservation—it’s about survival, according to the CGIAR Genebank Platform, wich led by the Crop Trust, enables CGIAR genebanks to fulfill their legal obligation to conserve and make available accessions of crops and trees on behalf of the global community under the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture.

Through the Platform, CGIAR genebanks safeguard a unique global resource of crop and tree diversity and respond to thousands of requests for germplasm from users in more than 100 countries worldwide every year.

When plant genebanks were created, they were intended to preserve genetic material (fundamentally gene combinations) with the aim that they might be used in the future , either directly or as material in breeding programs to face potential changes in environmental conditions or societal needs, even before discussions about climate change started.

After decades of experience with genebanks, the advantages and disadvantages of this strategy with respect to conservation in situ have been discussed extensively, according to a Spanish study in 2018, titled: “Plant Genebanks: Present Situation and Proposals for Their Improvement. the Case of the Spanish Network”.

To date, it seems that ex situ conservation has had more success than in situ conservation, probably because of its lower cost (about 100 times less than in situ conservation and greater ease for users to access the material.

Since the first plant genebanks were established, biological technologies have evolved immensely, so breeders now have more tools available to generate variability and also new data sources, according to “Frontier“.