Food & Climate

The Grand Egyptian Museum, which was inaugurated, November 1, 2025, reveals a part of the country’s history related to food production and how the ancient Egyptians preserved their natural resources, especially the Nile River water, from waste.

Among more than 100,000 artifacts, the Grand Egyptian Museum displays food utensils and some types of meals, of which wheat and barley were among the most important components.

The Grand Egyptian Museum was designed in a way that adheres to sustainability standards, in line with the spirit of the ancient Egyptians who were committed to protecting the environment, as documented in the papyrus scrolls. It saves the equivalent of more than 16 million liters of Nile water annually, according to the World Bank.

One of the texts from the Book of the Dead of the Egyptian pharaohs emphasizes the importance of preserving the Nile water, stating: “I did not pollute the waters of the Nile, nor did I act arrogantly towards others because of my position. I did not neglect a plant until it died of thirst, and I fed the hungry and gave drink to the thirsty.”

The Grand Egyptian Museum extends over an area of 500,000 square meters, located two kilometers from the three pyramids of Giza: Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure.

The energy and water-efficient design

The energy and water-efficient design of the Egyptian Museum tells the story of resource protection, including food, throughout the ages, especially wheat, as granaries for storing it have been known for centuries.

One of the most famous granaries was found in the Ramesseum Temple in Luxor. It was built with mud domes and lasted for 1500 years until the Roman invasion of Egypt, and was sufficient to feed Egypt and the Egyptian Empire that extended throughout the world.

The Romans nicknamed Egypt the “granary of the world.” Because “its wheat and bounty fed the world at that time,” Egypt continued to build granaries, with every city having a storehouse or silo until the era of the British occupation, which expanded cotton cultivation to meet the needs of its factories in Europe, as stated by the National Press Authority on its website.

The ancient Egyptians built granaries and storehouses from mud bricks, due to the need for ventilation of the grains, and they also revered the snake that eliminated the mice that threatened the granaries.

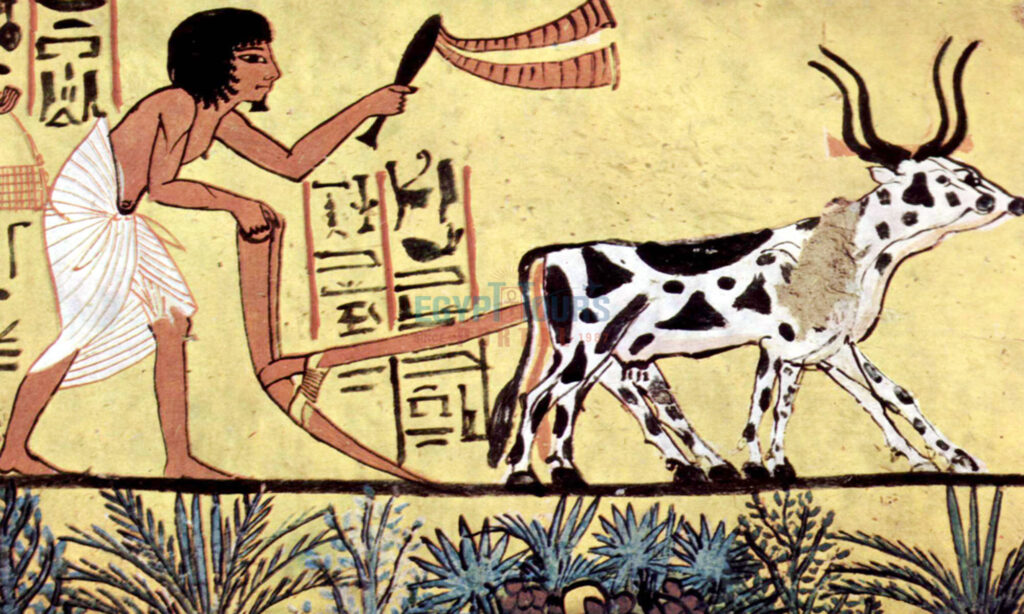

Wheat was one of the most important crops cultivated by the ancient Egyptians, and they produced a surplus for export, unlike the present time, where Egypt is the world’s largest consumer and importer of wheat, and does not produce more than 50% of its needs.

Because of the wheat shortage, workers protested in front of the grain silos at the Ramesseum during the reign of Ramses III, chanting words to the effect of: “We have nothing to eat”.

Due to the importance of wheat in the daily meals of the ancient Egyptians, they were keen to prevent price increases, as one of the texts in the Book of the Dead states, “I did not sell wheat at an exorbitant price… I did not cheat in measuring the grain.”

The cost of building the Grand Egyptian Museum

The cost of building the Grand Egyptian Museum reached $1.1 billion, equivalent to 51.7 billion Egyptian pounds, a huge figure for the Egyptian economy, especially since it increases the debt burden, even though most of the loans obtained were at concessional interest rates from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). However, throughout history, the country has overcome many crises, even at the level of food security.

According to research from Helwan University, food crises in ancient Egypt arose as a result of multiple factors, including: poor harvests, climate change, wars, and economic and diplomatic reasons.

The water level of the Nile River was unstable in ancient Egypt, sometimes falling and at other times rising, which caused frequent food shortages.

The ancient Egyptians knew how to manage these food crises, and the Egyptian and Ptolemaic rulers made efforts to maintain agricultural activities by building dams, digging canals, and storing and distributing food.

The study indicated that food crises were clearly documented during the First Intermediate Period through the autobiographies of rulers in the Ptolemaic era, such as those that occurred during the reign of Ptolemy III, recorded on the Canopus Decree, and during the reign of Ptolemy V on the Rosetta Stone.